Luke Goembel

By Scott Carlson

For The Towson Flyer

Originally published Oct. 6, 2016

Head down Regester Avenue in Idlewylde and you’ll see what looks like a repurposed real-estate sign with letters painted in bold red: “MOSQUITO SPRAYING KILLS BEES.”

And if you looked around to the backyard, you’d see several towers of wood boxes in honey-brown colors, with tiny insects buzzing around them.

The sign and the hives belong to Luke Goembel, a chemist, an inventor of spacecraft components, and, in the past couple of years, a fiery advocate for honeybees and other pollinators. With his training in science, he has plowed through technical reports, helping local beekeepers and environmental activists figure out if there is a link between pesticide use and the die-off of honeybees and other pollinating insects.

Goembel believes there is.

“I guess I found a niche for my skills in this whole ‘what’s killing the bees?’ thing,” says Goembel, sitting at a table in his sparsely furnished 1917 home. “Because I am a chemist, and I can read the papers, I can give my opinions.”

His work has made impacts — both close to home and statewide.

Luke Goembel’s bees

“I have had numerous conversations with people one on one who have mentioned Luke’s sign and their concern about the issue,” says Ben Larson, Goembel’s next-door neighbor. The message, Larson says, has been getting through. He has seen more people planting pollinator gardens and heard them talking about the impact of pesticides on bees. “It’s incredible how a simple homemade sign can make a big difference.”

Bonnie Raindrop, the legislative-committee chairwoman for the Central Maryland Beekeepers Association, says Goembel’s expertise was critical in getting the state to pass a ban on some kinds of neonicotinoids. Neonicotinoids, or “neonics,” are a class of powerful and widely used insecticides that many scientists and environmentalists believe contribute to bee colony-collapse disorder and die-offs among other pollinators. But they are also a major source of income for the pesticide industry. As the ban wended its way through the Maryland General Assembly, opponents to the bill presented papers claiming that neonics were harmless.

“Luke was able to show where they weren’t using sound science,” says Raindrop. Goembel also went to Annapolis to testify at hearings, meet with legislators to discuss the need for ban, and, with other beekeepers, stand outside the statehouse wearing his bee suit, holding vigil during the voting sessions.

Luke Goembel, far right, outside the Maryland State House with two other members of the Central Maryland Beekeepers Association with the Pollinator Protection Act’s Senate sponsor, Senator Shirley Nathan-Pulliam, second from left.

Goembel didn’t intend to become an environmentalist when he bought his first beehives. He started raising bees seven years ago, when he took classes on making mead. His interest in mead didn’t last, but apiculture presented fascinating challenges, like caring for the bees through changing seasons or dealing with the parasites and predators that can damage a hive.

Goembel, who got his doctorate in chemistry from The Johns Hopkins University in 1992, spent his career developing instruments that measure a spacecraft’s electrostatic potential, which could lead to arcing on the craft and the failure of its components. Raising bees seemed like a fitting hobby for his retirement.

“I like solving problems,” he says. Caring for bees is “a big puzzle.”

But the biggest puzzle came in May of 2015. After five years of raising bees with no trouble, Goembel started noticing that his forager bees — which fly out, looking for flowers — weren’t returning to the hive. The hive population was decimated.

“I felt like I was losing a child to a disease,” he says. [pullquote]The pesticide-regulation officer on the other end of the line brushed him off: “Your bees died. So what?”[/pullquote]

Through research, he determined that such a sudden collapse of foragers was likely caused by nearby pesticide spraying. He contacted people in his neighborhood, and found out that mosquito sprayers had fogged a number of yards in the area. Through more research, he learned that the companies used chemicals and techniques that killed indiscriminately, affecting both “bad” insects and beneficial ones.

He called the Maryland Department of Agriculture to raise alarm about the sprayers, but the pesticide-regulation officer on the other end of the line brushed him off: “Your bees died. So what?” Goembel says, recalling the gist of their conversation.

That blasé response launched Goembel into activism. In recent years, beekeepers have seen die-offs of 40 to 60 percent of their hives. That figure is unsustainable — both environmentally and financially for apiarists who raise bees for a living. Imagine, Goembel says, if half of a dairy farmer’s cows died every year. Last month, after a county in South Carolina sprayed an organophosphate called Naled in an attempt to kill mosquitos carrying Zika, one apiary lost 46 hives, or roughly 2.5 million honeybees.

Luke Goembel with his hives

But pesticides are not just affecting honeybees. Honeybees are just one of about 20,000 species of bees in the world. A variety of other animals — including wasps, beetles, butterflies, bats, and birds — act as pollinators in addition to wild and domesticated bees.

The pesticides add to various pressures already affecting those pollinators, like the destruction of foraging habitat. A United Nations-sponsored report released earlier this year said that 40 percent of invertebrate pollinators — insects like bees and butterflies — are facing extinction.

And just this week seven types of bees were put on the U.S. Endangered Species list — the first time bees have ever been on the list.

That’s bad news for plant life of all kinds: About a third of the food we eat depends on pollinators. Some fruits, grains, and vegetables — like watermelons, squash, kiwis, cashews, buckwheat, and many more foods — absolutely depend on pollinating insects to produce.

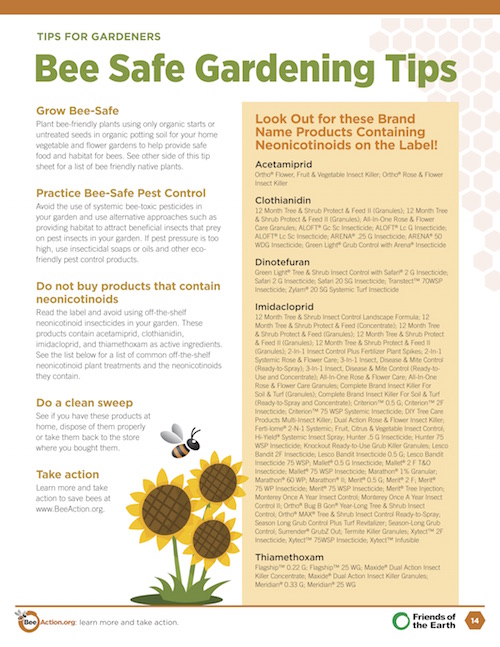

Earlier this year, the General Assembly passed the Pollinator Protection Act of 2016, which will take 300 consumer-grade, home-gardening products containing neonicotinoids off shelves in Maryland by 2018. (Maryland’s legislature was the first to pass such a bill, but the state was not the first to make it a law. While Gov. Larry Hogan sat on the bill, neither signing nor vetoing it, Connecticut established a ban on neonics.)

Goembel and others from the Central Maryland Beekeepers Association worked with 70 groups — including bird clubs, public-health researchers, clean-water organizations, and sustainable farmers — to advocate for the ban. But the opponents brought their own forces: In the 2015 session, Bayer CropScience, a division of the German multinational chemical and pharmaceutical company, sent a scientist to testify against the act.

This year, the Maryland Department of Agriculture also opposed the ban, arguing that it would be costly and burdensome. The supporters had to make a concession to see the regulation passed: Gardening stores will not have to label the products containing neonics nor the plants that have been treated with them. (Once treated with the chemical, plants can remain toxic to pollinators for years.)

Next week, Goembel and others from the Central Maryland Beekeepers Association will be honored with the John V. Kabler Environmental Leadership Award from Maryland League of Conservation Voters for their work on the law.

Goembel tallies the bill’s passing as a win, but challenges remain for his backyard colony. Mosquito sprayers still occasionally cruise through the neighborhood. Groomed suburban yards can be nearly devoid of plants beneficial to bees. And there are always diseases, pests, and predators to deal with.

That’s where Goembel’s knack for invention might come in handy. He won a first-prize ribbon in the “bee gadgets” category at the Maryland State Fair for his design of an “oil-trap bottomboard,” a device that captures honey-eating beetles and drowns them in oil. He drips a solution of sugar and oxalic acid — a chemical found in vegetables like cabbage and rhubarb — onto his bees to kill off Varroa destructor mites. He has designed moats filled with oil to prevent ants from invading his hives. Many of these techniques have been used by other beekeepers, Goembel says, but he often builds his own devices and mixes his own concoctions, which might make his approach unusual. [pullquote]“Some of the stuff that he does is not by the book, but damn, it seems to be working for him.”[/pullquote]

“It used to be, 30 years ago, you bought bees and you put them in a box, and you went back and gathered the honey in the fall,” says Arnie Breidenbaugh, the president of the Central Maryland Beekeepers Association. “Now bees have to be treated like livestock. You have to monitor their health, mite loads, disease, viruses, pests — and you have to treat for all of these things as needed.”

Goembel, Breidenbaugh says, has been a remarkably successful beekeeper: He bought two packages of bees seven years ago and has managed to keep those bees (and their descendants) alive for seven years.

“I have to buy bees almost every year, especially the past three or four years. They just do not come through the winter,” says Breidenbaugh, who started keeping bees in 2001. “Some of the stuff that he does is not by the book, but damn, it seems to be working for him.”

Goembel spoke to the Central Maryland Beekeepers’ Association last month at Oregon Ridge, detailing some of his techniques, and this week he spoke to a beekeepers’ association in Frederick County. He says he wants to help other apiarists find the kind of success he has had. Replacing hives each year can be prohibitively expensive, even for hobbyists.

As for Goembel’s own hives, they have recovered from last year’s die-off. In June, he harvested 117 pounds of honey that he will eat, give to friends, and sell at a discount to neighbors. He has seen almost no mosquito-spraying trucks cruising the neighborhood, and fewer signs advertising their services in nearby yards.

“Right now,” he says, “I have four very healthy hives for going into winter.”

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE:

http://towsonflyer.com/2017/07/29/bcpl-now-free-movie-streaming-home/

The sign should say “spraying for mosquitos incorrectly kills bees”.

If done correctly (at dawn & dusk), the risk to bees is fairly low.

Except that all the companies I have seen doing it are out there in the middle of the day, spraying everything.